Saturday, August 29, 2009

Definitions

Regime: Institutions, formal or informal, of access to the state (i.e., to the control of resources that back up political decisions). Examples: in a democracy, the form of access to the state is elections (competitive and participatory).

Government: Specific group of people in control of the state. E.g.: Bush Jr government, or Obama government. State and regime remain the seam, but the team of people in charge changes.

Now, finally, Revolution: is it a change in government, regime, or state? Does it involve broader social change?

Think about the revolutions that we know:

Latin America Independence Revolutions: change in all three political levels, including the state, (because new territories are created, different from the old Iberian Empires), but no social change.

Soviet Revolution: change in Regime, Government, and Society, but not in the State (which in the beginning has the same old Russian territory).

French Revolution: paradigmatic case of regime change, but no change in state (France remains France). Change in social order? Yes, no more aristocracy.

American Revolution: change in State (the British empire breaks up), but not too much social change.

Mexican Revolution: no change in state, change in government and regime (but from one subtype of dictatorship to another subtype, caudillo to party), and broad social changes, which nevertheless fall short of socialism.

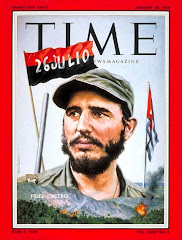

And the Cuban Revolution?

Wednesday, August 26, 2009

Jokes about Castro's immortality and death

Castro has died, and his body is lying in state. Mourners have lined up to pay their respects. At the head of the line is Felipe Pérez Roque, Cuba’s forty-one-year-old Foreign Minister, who is often called Felipito. (Behind his back, he is also called a Taliban.) Pérez Roque stands before Castro’s coffin, his head bowed, while Ricardo Alarcón, the president of Cuba’s National Assembly, waits his turn. The minutes drag on; Alarcón becomes impatient and taps Pérez Roque on the shoulder, whispering, “Felipito, what are you waiting for? He’s dead, you know.” Pérez Roque whispers back, “I know he is; I just haven’t figured out how to tell him that.”

Friday, August 21, 2009

The "Accidental" Fall of the Berlin War

WSJ, Oct 21 2009

Did Brinkmannship Fell Berlin's Wall? Brinkmann Says It Did Reporter Claims He, Not an Italian Competitor, Caused an Apparatchik to Err and Open Border

By MARCUS WALKER

BERLIN -- The world believes Ronald Reagan, Mikhail Gorbachev or peaceful protests brought down the Berlin Wall 20 years ago next month. But for those who had front-row seats, the argument boils down to Ehrman vs. Brinkmann.

Riccardo Ehrman, a veteran Italian foreign correspondent, and Peter Brinkmann, a combative German tabloid reporter, both claim they asked the crucial questions at a news conference on Nov. 9, 1989, that led East German Politburo member Günter Schabowski to make one of the biggest fumbles in modern history.

Mr. Schabowski was supposed to announce a temporary bureaucratic procedure that would make it easier for East Germans to travel abroad, a tactic aimed at shoring up the Communist regime in the face of mass demonstrations.

Instead, he inadvertently opened the Berlin Wall (emphasis added by SM).

When his fellow Communist leaders decided on new travel regulations, Mr. Schabowski was out of the room. Later that evening he skim-read the executive order, stuffed it in his briefcase, and headed off to meet the world's media.

Pressed on the meaning of the new travel policy -- When did it come into force? Did it apply to West Berlin? Did people need a passport? -- the flustered apparatchik rustled his papers and gave confusing answers that led the news media to believe the border was open, with immediate effect.

The result, once East Berliners had seen that night's news on West German television, was chaos at border crossings across the city.

East and West: As the Berlin Wall Fell

At Bornholmer Strasse, one of the main checkpoints in central Berlin, confused border guards couldn't get clear orders on how to deal with the crush, and debated whether to open fire. Instead, they opened the barrier, and the Berlin Wall was history. The events have been chronicled by Hans-Hermann Hertle, a historian who specializes in the fall of East Germany.

As the anniversary of that tumultuous night nears, a dispute is heating up over who flummoxed Mr. Schabowski.

Among those who are aware of the incident, Mr. Ehrman generally gets credit. In 2008, Germany's president awarded Mr. Ehrman the country's highest honor, the Federal Cross of Merit. "His persistence at the press conference finally elicited the crucial statement" that brought down the Wall, the citation said: "His name stands for...German unity."

Mr. Ehrman, now 80 years old and retired, recalls asking the first question about freedom to travel, and the first follow-up questions that rattled the Politburo spokesman.

"The surprising fact is that I apparently was the only journalist in the room who understood the meaning of Schabowski's words," Mr. Ehrman says.

He remembers quickly leaving the press conference and sending his employer in Rome, news agency ANSA, the headline: "The Berlin Wall has collapsed." His editor there said he had gone pazzo, crazy, and at first refused to run the story.

That heady night, cheering East Germans queuing to pass through the Wall recognized the Italian from TV and hoisted him onto their shoulders.

But Mr. Ehrman is puffing up his role, says Mr. Brinkmann, who worked for Bild-Zeitung, Germany's mass-selling tabloid, famous for its shrill headlines, short articles and topless front-page models.

Mr. Ehrman merely posed a question about a previous travel proposal, Mr. Brinkmann says. The crucial questions about timing and West Berlin were his alone, he says.

And while Mr. Ehrman was being feted that night, Mr. Brinkmann, by his own account, wasn't yet done bringing down communism. He says he secured the opening of Checkpoint Charlie, the Wall's most famous crossing, by arguing with its guards.

When his rival got a medal, a decision Mr. Brinkmann calls "nonsense," Mr. Brinkmann wrote the German president to set the record straight.

"The annoying thing is you can't see me on the TV footage -- you can only see Ehrman and Schabowski -- but you can hear me," says Mr. Brinkmann. He adds, for anyone who thinks it is the Italian posing questions, that it is "funny how Ehrman suddenly develops perfect German" during the exchanges.

Mr. Brinkmann thought he had picked the best seat in the house: front row and center. The German tabloid reporter occupied the chair with his jacket three hours before the news conference in East Berlin began.

Mr. Ehrman arrived so late that all seats were taken, so he sat on the edge of the podium, in full view of the cameras.

Mr. Brinkmann, now 64, is trying to fight his way into the history books with a public-relations offensive. He has persuaded some historians and TV documentary makers of his story, and he is spreading the word on Twitter.

"Am angry that Riccardo Ehrman falsely gets the credit for calling out 'When? Immediately?' when the Wall fell in 1989," Mr. Brinkmann tweeted recently.

Mr. Ehrman counters that he has never even heard of Mr. Brinkmann. "Anybody is free to claim whatever they like, but the record is clear," Mr. Ehrman says. "It was a sort of conversation between Schabowski and myself. This, Schabowski admits."

Mr. Schabowski, now 80, has been in and out of hospital this year and is too sick to give an interview. Mr. Brinkmann is trying to get the ailing former East German Politburo member to sign a statement backing his version. "Then I can show everyone," Mr. Brinkmann says.

Mr. Ehrman says he is offended that some German media and historians have recently cast doubt on his role in 1989. "Some said it was just a fluke, while others said I was a tool of the [East German] regime," he says.

Archive footage from East German TV packs some surprises that nobody quite remembers. For an hour, the press conference is a nonevent. In a cramped room clad in the Soviet bloc's regulation brown paneling, Mr. Schabowski rambles on about the party leadership's deliberations that day.

With time running out, Mr. Ehrman asks about travel restrictions. Mr. Schabowski drops the bombshell that the regime has decided to allow East Germans to travel west or emigrate.

Three reporters launch a rapid-fire cross-examination: Mr. Ehrman, Mr. Brinkmann -- and Krzysztof Janowski, a political refugee from Communist Poland who worked for Voice of America (and who now says he doesn't remember details of the day). Together, the trio cause Mr. Schabowski to scratch his head and read his brief aloud, learning its content himself as he goes.

Finally, a fourth voice draws Mr. Schabowski's eyes to the opposite side of the room. The voice repeats the key question: "When does that go into effect?" The Politburo member scans his papers and quotes words out of context: "Immediately. Without delay," he blunders.

The fourth man has never been identified.

-- Almut Schoenfeld contributed to this article.

Write to Marcus Walker at marcus.walker@wsj.com

Excerpt: Asking the Hard Questions

Gunter Schabowski was supposed to announce eased travel restrictions for East Germans. Instead, his answers left reporters with the impression the Berlin Wall had fallen. Here's an excerpt from the Nov. 9, 1989, news conference:

Riccardo Ehrman (reporter, ANSA): Don't you think it was a big mistake, this draft law on travel that you presented a few days ago?

Gunter Schabowski (East German Politburo official): No, I don't think so. Ah... [talks for three minutes] And therefore, ah, we have decided on a new regulation today that makes it possible for every citizen of the GDR, ah, to exit via border crossing points of the, ah, GDR.

Ehrman: Without a passport?

Krzysztof Janowski (reporter, Voice of America): From when does that apply?

Schabowski: What?

Peter Brinkmann (reporter, Bild): At once? At...?

Schabowski: [Scratches head] Well, comrades, I was informed today …[puts on his glasses, reads out press release on visa authorization procedure]

Ehrman: With a passport?

Schabowski: [Reads out rest of press release, says he doesn't know the answer on passports]

Second East German official: The substance of the announcement is the important thing...

Schabowski: ...is the...

Fourth reporter: When does that go into effect?

Schabowski: [Rustles through his papers] That goes, to my knowledge, that is...immediately. Without delay.

Third official: [Quietly] That must be decided by the Council of Ministers.

Janowski: Also in Berlin?

Brinkmann: You only said the FRG, does this also apply for West Berlin?

Schabowski: [Reads] As the press department of the ministry...the Council of Ministers has decided that until the People's Assembly enacts a relevant law, this temporary regulation will be in effect.

Brinkmann: Does this also apply to Berlin-West? You only said the FRG.

Schabowski: [Shrugs, frowns, looks at his papers] So...yes, yes: [reads] 'Permanent exit can take place via all border crossing points of the GDR to the FRG or to Berlin-West.'

Footnote: GDR = German Democratic Republic or East Germany; FRG = Federal Republic of Germany or West Germany

Sources: DDR1 archive footage, WSJ research

![[Brandenburg Gate]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/P1-AS134_Heros_F_20091020171550.jpg)

![[SB10001424052748704500604574485591011878208]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OB-ES058_heropr_D_20091020161315.jpg)